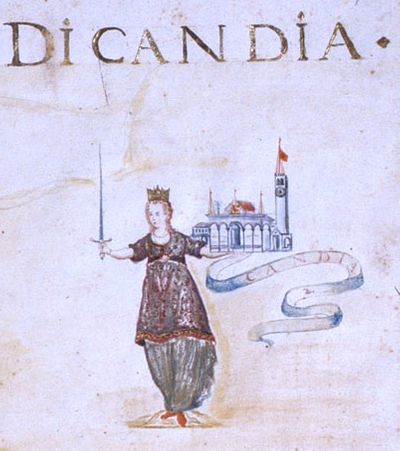

Welcome to the CuRe (Cultures and Remembrances) app, highlighting cultural encounters on Crete from the 13th to the 20th century. Users are offered a series of routes to sites of remembrance (lieux de mémoire) connected to three periods in Cretan history: Venetian rule (13th-17th century), Ottoman rule (17th-19th century) and the German Occupation (1941-1944/1945). While Venetian times were hallmarked by the coexistence of different Christian denominations, and the Ottoman period by the concurrence of different religions, the Occupation years saw a clash between two opposing ideologies.

The Venetian period began in the early 13th century and ended in the Cretan War (1645–1669). Early Venetian rule was marked by the Orthodox population’s fierce resistance to the Catholic overlords, though peaceful coexistence subsequently took hold. Venetian civic cuure ultimately won over the Orthodox Cretans, while successive Venetian-Turkish wars and the manifest expansionist tendencies of the Ottomans served to unite the main population groups. For the Venetian period we have planned five routes leading into the towns and hinterland of Rethymno and Heraklion, with sights and places of memory that give an idea of town and country life. App users can tour private houses and representative Venetian government buildings, coming into contact with everyday life in the towns, public utility projects and fortification works, Catholic order monastery complexes and so on. Similarly, in the countryside, they can visit monasteries and impressive churches attended by the “Roman”-Cretan (i.e. Byzantine-origin) nobility and the Orthodox population, and learn about buildings with engravings, inscriptions, architectural decoration, reliefs, wall paintings and burial monuments. The surviving mediaeval monuments are reference points for the fiefs and pre-industrial installations within settlement networks. All of the above are depicted in the app with examples linked to archive material and contemporary literary sources, and placed within the topography defined by the administrative setup of the time. In this way, present-day visitors can get a taste of everyday life in rural communities: the life of Venetian Cretans, as well as that of the Orthodox Cretan “Roman” population, their view of the common past, their identity and the claims staked on either side, in what was a multicultural Crete.

Many Venetian buildings were remodelled and put to different use by the Ottomans. The German invading army also made use of iconic historic buildings. To highlight the appropriation mechanisms used by each wave of conquerors, we have set up the Venetian and Occupation routes in Heraklion along parallel lines, so that they lead to the same points and same buildings. The app makes occasional use of historical names for places and buildings that may since have changed.

The Ottoman period route follows in the footsteps of the 17th century Ottoman traveller Evliya Çelebi, who set out on his peregrinations from Constantinople in 1631; from 1640 he spent almost forty years touring many parts of the Ottoman Empire and areas beyond its borders. Several of his journeys were made in the service of pashas who had assumed office as regional governors or had been dispatched to foreign courts as emissaries of the sultan. The Ottoman traveller recorded his journeys in the Seyahatname or Book of Travels, which is subdivided into ten further books. Evliya Çelebi’s vivid work is a mine of information, though not always systematic, detailed or accurate: the author is prone to exaggeration and boasting; the numbers he records express orders of magnitude rather than precise quantities; he cites legends as if they were historical facts; and he occasionally describes places, sights and events as if he were an eyewitness, despite having actually garnered information from other written or oral sources. At any rate, the Seyahatname remains a valuable historical source, and one extensively used by contemporary historians. Beyond the information it provides on the cities visited and the lives of their inhabitants (his narrative mainly concerns urban space), the book is testimony to the worldview of a pious, literate 17th century Muslim in the ranks of the Ottoman social elite. The information to be found in Evliya Çelebi’s work, which is devoid of illustrations, mainly concerns the history of a town or area, its public and private buildings, its public officials and members of the elite and local culture, ranging from the language and religion of the locals to their attire and food, as well as anything else the author considered curious, entertaining or worthy of mention.

Evliya Çelebi was on Crete between 1668 (or early 1669) and 1670, coinciding with the final phase of the Ottoman siege of Candia and the Venetian surrender to the city’s new masters. The author also claims to have visited the island in 1645, at the beginning of the Cretan War, though that is contested by contemporary researchers. Çelebi disembarked at Chania in 1668 (or 1669), and headed east, passing through Rethymno on his way to İnadiye (the Ottoman camp to the south of Candia, on the site of what is now Fortetsa), and to Candia itself (modern-day Heraklion).

As part of CuRe, the app offers visitors to Crete information on monuments and other Cretan landmarks in Chania, Rethymno and Heraklion Regional Units, with emphasis on the island’s three main cities. The starting point is Evliya Çelebi’s outlook, enriched with more general information on the features and historical developments of the monuments in hand. The routes suggested by the CuRe app have been designed to facilitate visitor tours, and do not follow the order in which Evliya Çelebi records monuments and other landmarks in his work. CuRe users can either select individual monuments or follow a route from any point they wish. Brief details of the historical figures referred to at the various stopping points are given, together with explanations of Ottoman terms, though such information only appears the first time people and terms are encountered on the suggested routes.

Recommended reading for those interested in learning more about Evliya Çelebi and his work includes the following: Robert Dankoff, An Ottoman Mentality: The World of Evliya Çelebi, With an Afterword by Gottfried Hagen, Brill: Leiden and Boston, 2006; Elias Kolovos, “Στα μετόπισθεν των πολιορκητών του Χάνδακα: η ‘πολεμική ανταπόκριση’ του Εβλιά Τσελεμπή”, Cretica Chronika, 39 (2019), pp. 357-379.

Two routes subdivided into sections are suggested for the German Occupation period. Setting out from Rethymno, the first takes users to the town’s eastern outskirts and on to Amari and Agios Vasilios. The second route heads from Heraklion to the southern part of the Regional Unit Heraklion up to Agia Galini (which belongs to Rethymno Regional Unit) and back. The Occupation routes have 76 stops in all, linked to war operations, acts of resistance, reprisals against the people of Crete, forced labour and everyday life under the Wehrmacht. To highlight Occupation sites of remembrance, we have drawn on over 100 Greek, German and English-language sources (autobiographical texts, interviews and testimonies, propaganda material, newspapers and historical works), and used over 260 photographs past and present, as well as drawings from private and public archives. Drawings and photographs in the archive compiled by one-time Wehrmacht soldier Rudo Schwarz and now held by the Society of Cretan Historical Studies form the backbone of the route planned from Heraklion to Agia Galini via Knossos and the Messara Plain. At some points on the routes there is nothing more than a plaque commemorating the historical events, or traces of destruction and dereliction.

Some details may confuse users, such as the multiple variants and forms of names for people and places that appear in sources and in the app. There are several reasons for this: in Greek sources, the names are encountered in different forms (e.g. the Asomatoi Monastery and the Asomatoi School are the same, as the monastery was converted into an agricultural college in the 1920s). Certain Greek sources use more learned forms of names, while others use informal ones (e.g. Georgios, Giorgos, Giorgis). Added to this, of course, there is the perennial problem of transliteration from Greek; though some standardisation has been applied, varying renditions may occur in texts by different authors.

Stops further along routes presuppose familiarity with information given at earlier ones. That apart, users can pick up the thread of a route from any stop without missing out on its underlying logic – just as one might start watching a film some minutes into the action.